Iowa Sikh Association

CONTACT

HOURS

ETIQUETTE

Leader(s): Unspecified

Phone number:

+1 515-537-2971

Email:

Website: [www.iowasikhassociation.org]

(http://www.iowasikhassociation.org)

Regular services are held on Sundays.

The temple is open every day from 7 am-6 pm.

Remove your shoes before entering the prayer hall.

Cover your head inside the gurdwara (head coverings are usually available at the entrance).

Dress modestly.

Sit on the floor during services.

Participate in or respectfully observe langar (community meal) after the service.

Avoid bringing tobacco, alcohol, or drugs onto the premises.

Student Testimonial

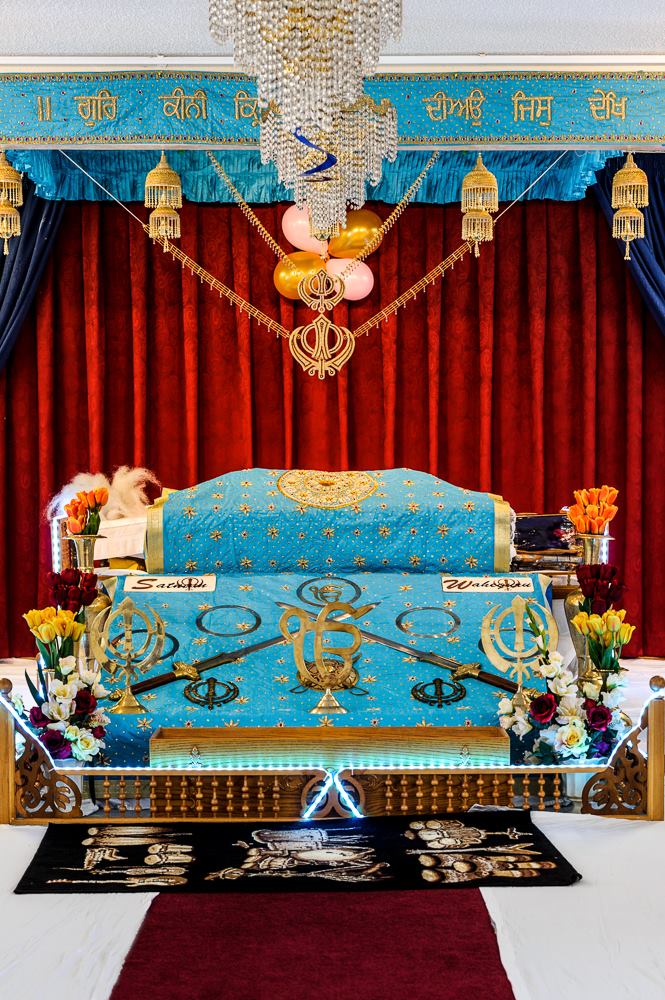

The Iowa Sikh Association is a religious and cultural organization that serves the Sikh community in and around Des Moines, Iowa. It provides a place of worship, community gathering, and education about Sikhism. The association organizes religious services, cultural events, and educational programs aimed at promoting understanding and unity. The gurdwara (Sikh temple) is open to everyone, and the community emphasizes the core Sikh values of equality, service, and devotion.